Francesca Gavin on the History of Collage

The first in a two part series, curator and writer Francesca Gavin documents the beginnings of collage to the consumer boom in postwar America

Think about how you look at the world. It is not a linear, coherent experience. Instead, it is a melange of snippets of movement and angles, interspersed with blinking and put together into something logical by your brain. Collage is a technique that most closely reflects perception. Over the past century, the layering, arranging, cutting, recombining, and gluing of imagery and things have become the defining approach to making art.

Collage combines some of the fundamental aspects of the now. It is a space to examine desire. To look at the reduction of the body as a fragmented part and remake these broken elements into something whole. Collage is a place to access fantasy and utopia. A place to create unexpected encounters and conversation. To resist, to dismantle socio-political structures, and critique the media machine. It reflects the joy of vandalism and the pleasure of making.

While often seen as a 20th-century medium, the beginnings of collage were far earlier than most people think. Japanese calligraphers pasted poems onto sheets of paper in the early 12th-century, such as the Iseshu manuscript, which decorates pages with birds or stars made from gold or silver paper or sets things against torn or cut colored paper to represent landscapes. In Western Europe, genealogical registers included cut-and-paste heraldic imagery in the 1600s. From the 17th-century, creating cut-and-paste silhouettes and decorative paper collages for devotional pictures in prayer books was a popular pastime for women. By the 18th-century, this had developed into love tokens.

'Sheela’s Syrian Goddess of Opening Up' by Mary Beth Edelson. 20.3 × 25.4 cm 1973. (Work: Mary Beth Edelson, The Age of Collage 3)

Collage moves hand in hand with developments in print culture, and the rise of more easily accessed engravings and lithographs. The industrialization of printing in the 19th-century changed how and who could access printed imagery. Valentine cards were born. The decoupage became a craze. People, mostly women, would decorate folding screens and chests, or fill scrapbooks with prints, fashion plates, flowers, poems, postcards, theater handbills, and newspaper cuttings. The passion for decoupage was so profound that by the 1880s people could buy ready cut, color-printed, chromolithographic glazed scraps. The collage aesthetic was also used in advertising posters, especially those produced by the Beggarstaff Brothers ad agency in London. Photomontage had also been part of visual culture since the 1850s, originally in newspapers and later in commercial publicity and travel postcards. When artists started working with collage, it was this commercial and feminine history that they were drawing on.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque’s experiments with collage between 1908 and 1912 have often been positioned as "ground zero" for collage as an artistic medium. As critic Clement Greenberg put it, Cubism was the “turning point in the whole evolution of modernist art.” Their experimental works crossed the border between reality and what was being depicted. Art’s relationship with illusion fell apart. The lofty intentions of fine art became fused with everyday culture. Instead of an image of café life, they inserted elements from cafés into the work. The paint was combined with pasted sections of sheet music from popular songs, papers printed with fake wood and scraps of newspapers. Picasso and Braque’s work, and later that of Juan Gris, was also political, reflecting the sociopolitical melange of café culture, the central role of newspapers in politics, and the uneasy rise of anarchism and socialism. As Picasso later told his partner François Gilot, "The world was becoming very strange and not exactly reassuring."

The Cubists did not invent collage. They were undoubtedly aware of the craze for decoupage and how newspapers were using photographic material. However, what was revolutionary was their attitude. They established collage as the methodology of modernity. They showed how the environment emotionally, intellectually, and politically spilled into what Daniel Belgard calls the "body-mind." Their work reflected the social mobility and energy of urban café life. Coller, to paste, became a process of utopian possibility.

The First World War was a creative catalyst for the century. The industrialization of the war machine and the absurdism of the political decisions left a broken European landscape covered in detritus and decay. Figurative painting seemed a prewar fantasy that had no relevance in the modern world. Dadaism emerged, using collage as a creative form of political critique. Hans Arp had been in Paris in 1914, avoiding the German draft, before fleeing to neutral Zürich where he exhibited collage in 1915. In 1916, George Grosz and John Heartfield collaborated on care packages for soldiers at the war front. These included absurdist collage works containing messages decrying war, shallow consumerism, and trivial pleasures. Kurt Schwitters began to make collages from scraps picked up on the street in 1918. Hannah Höch drew on her editorial experience in the creation of her aesthetics. She had worked at the women’s magazine Die Dame between 1916 and 1926, designing handiwork patterns, and the publication became a source for her collages. These artists used the technique to renounce the structures of society, the values of life and truth, and express their alienation and dissent—often with a dose of humor.

'Starting At Hell' by Lola Dupre. 29.2 × 41.9 cm 2020. (Work: Lola Dupre, The Art of Collage 3)

The desire for upheaval can also be seen in the futurist collage work coming out of Italy, and the constructivist movement in post-revolutionary Russia. Both movements used collage to combine aesthetics with slogans of war or political propaganda. The violence of the medium was a perfect reflection of the trauma and violence of postwar Europe. While the revolutionary movements of early Modernism drove experimentation in collage, Surrealism has had the most lasting influence on the medium. Collage was perfect as a platform for Surrealism’s conceptual approach, an outlet for the desire for the unexpected and uncanny. Surrealists took the absurdism of Dada and added poetry and magic to its incoherence. Collage could address the representation of dreams, free association, and social commentary, and could be used to critique the power structures the Surrealists hated so much, notably sex and religion.

In his 1930 essay, The Challenge to Painting, Louis Aragon positioned collage as fundamental to the evolution of art. It presented a possibility. “Art has truly ceased to be individual,” he wrote. "Plagiarism is necessary. Progress involves it. It adheres closely to the author’s words, makes use of his expressions, erases a false idea, replaces it by a correct one." Aragon curated an exhibition of collage work in the same year as his essay, including Man Ray’s photographs and Magritte’s paintings, which were both collage-like in conception and aesthetics, even if they did not include cut-up material directly. For the poet and critic, collage presented a way to draw from the "poor" and reproducible with endless outcomes. As he noted, "To be well made, a maxim does not need to be corrected. It needs to be developed."

For Max Ernst, collage provided direct access to the unconscious. Reworking printed illustrations allowed him to reveal his "most secret desires" out of "banal pages of advertising." His series La Femme 100 Tetes takes the monochrome engravings from 19th-century novels and transforms the bourgeois into fantasy. "What is the noblest conquest of collage?" he asked in 1936. "The irrational." Ernst returned to the medium throughout his practice, varying his style but always coming back to the juxtaposition of image.

The United States embraced the medium in the 1940s, sparked by Peggy Guggenheim’s support and exhibitions of Surrealist collages. Joseph Cornell made his name with sculptural collage works. His three-dimensional boxes resemble small wunderkammers filled with strange things. The reference art history while expressing the hallucinatory nightmare of American reality. The abstract expressionist artists of the 1950s also experimented with collage, especially Lee Krasner, Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers, and Anne Ryan. Krasner, for example, used her own discarded paintings and those of her partner, Jackson Pollock, as scraps to rework, noting, "My collages have to do with time and change."

Consumerism exploded in the postwar United States. The century had seen a rise in commercial print ephemera, reflecting cheap printing costs and the advent of color photography. By the 1950s, the commercial and advertising machine was at full throttle and quickly began co-opting collage as a visual technique to snare consumers. It was against this backdrop that Robert Rauschenberg began to work, initially with sculptural assemblage and then with the screen-printed layers of found photographic material that he became so famous for. He used fragmented images yet retained their identity. Images of war, socio-political unrest, and technological changes were transformed into something creative and new—like the fading memory of a dream after waking.

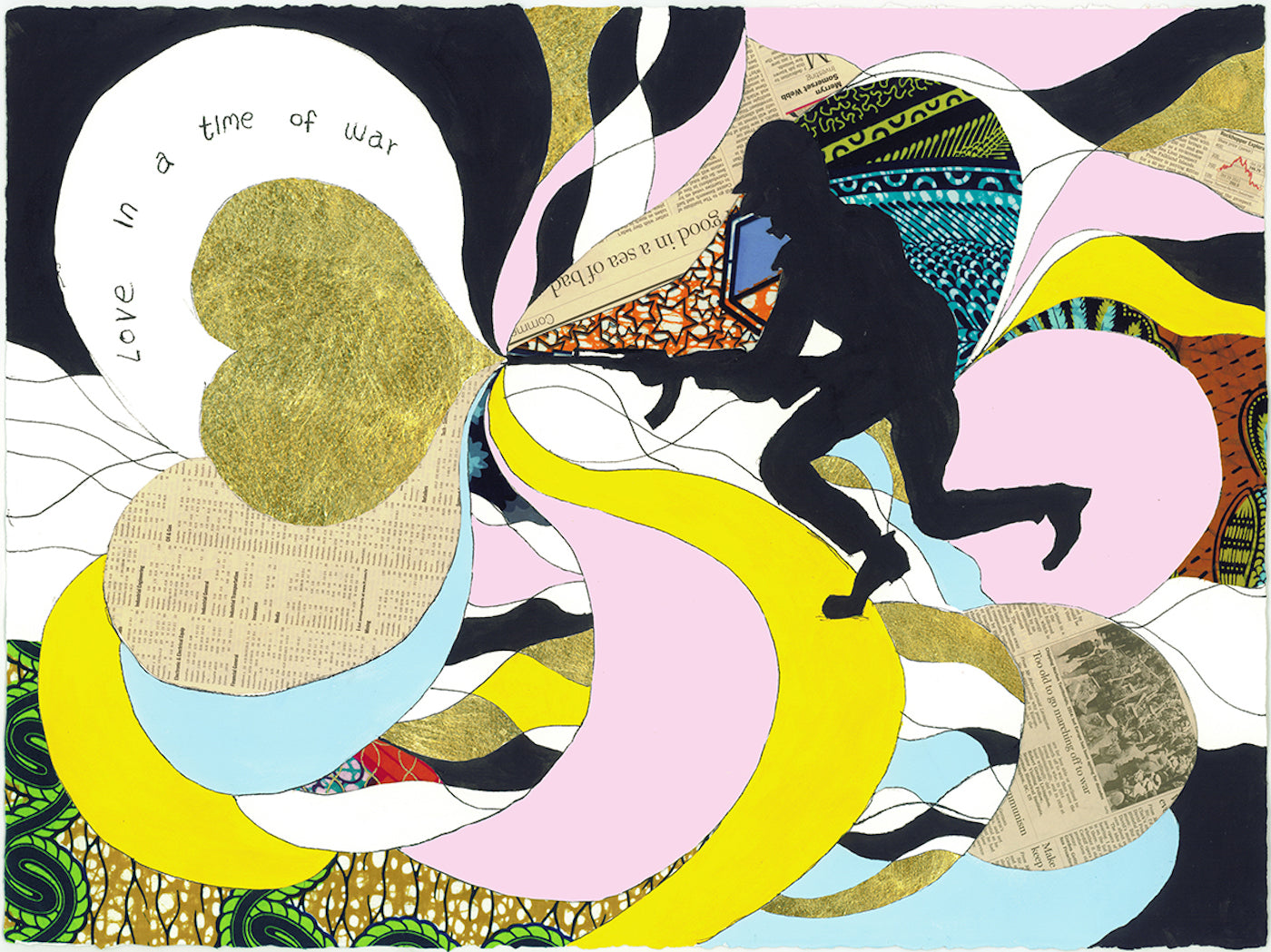

Jump into an art form which is shaping visual communication in ever new and provocative ways through The Age Collage 3.