Architecture is for Listeners

To celebrate Isay Weinfeld's 67th birthday today, we look back at an essay from Brazilian writer and journalist Raul Juste Lores featured in our book

“I don’t treat architecture as a religion,” says Isay Weinfeld. Isay doesn’t like dinner parties where all the guests are fellow architects. He’d rather be surrounded by musicians, actors, filmmakers, journalists, and those that add unexpected and thought-provoking conversation to the mix.

Clube Chocolate opened its Sāo Paulo branch in 2003 with the help of Weinfeld. A sandy beach was sawn into the long narrow site, alluding to a seaside scene connected to the boutique store's origin, Rio de Janeiro. (Photo: Alvaro Povao)

Born on October 21, 1952, Weinfeld doesn’t enjoy talking about architecture for too long. His countrymen, such as Oscar Niemeyer and Paulo Mendes da Rocha, might favor political discussions over talk of their projects, but Isay, as he’s known in his native Brazil, gets more excited about other passions. It is no surprise that there are many of them.

One might think he is a maestro based on his love of music. One of his deepest fears is to lose his hearing; in his words, “To hear is the greatest talent an architect should have.” He can spend hours debating the latest Radiohead album, or discussing Japanese cuisine, plays directed by his friend, theater director Felipe Hirsch, and the most recent releases in the cinema. Isay avoids repetition, predictability, and boredom.

Casa das Figueiras seems to weave itself into the jungle floor beneath it in some areas of the house. The home was completed in 2013 by Weinfeld, it strikes a balance out of many contrasts: between indoor and out, light and dark, natural and man-made. (Photo: Fernando Guerra)

Fortunately for him, he came of age in the seventies, when the weaknesses of modernism had already been exposed. Even brutalism—particularly embraced by São Paulo’s architects from the early 1970s until the early 1990s—started to show cracks in its not-so-well-maintained raw concrete walls. Isay dared to distance himself from making anyone style his own. A concrete-box house with glass windows and some Barcelona chairs is a formula punishable by his own karma police.

I remember the impact of visiting, for the first time, his Forum flagship store (2000) in his native São Paulo. The two wings of the fashion space, for men and women’s clothes, meet in a dramatic staircase covered with red glass glossy tiles. On the top of the stairs was a bar, the wall behind it was made of taipa, a mixture of clay and dried vines that were used in colonial-era Brazil.

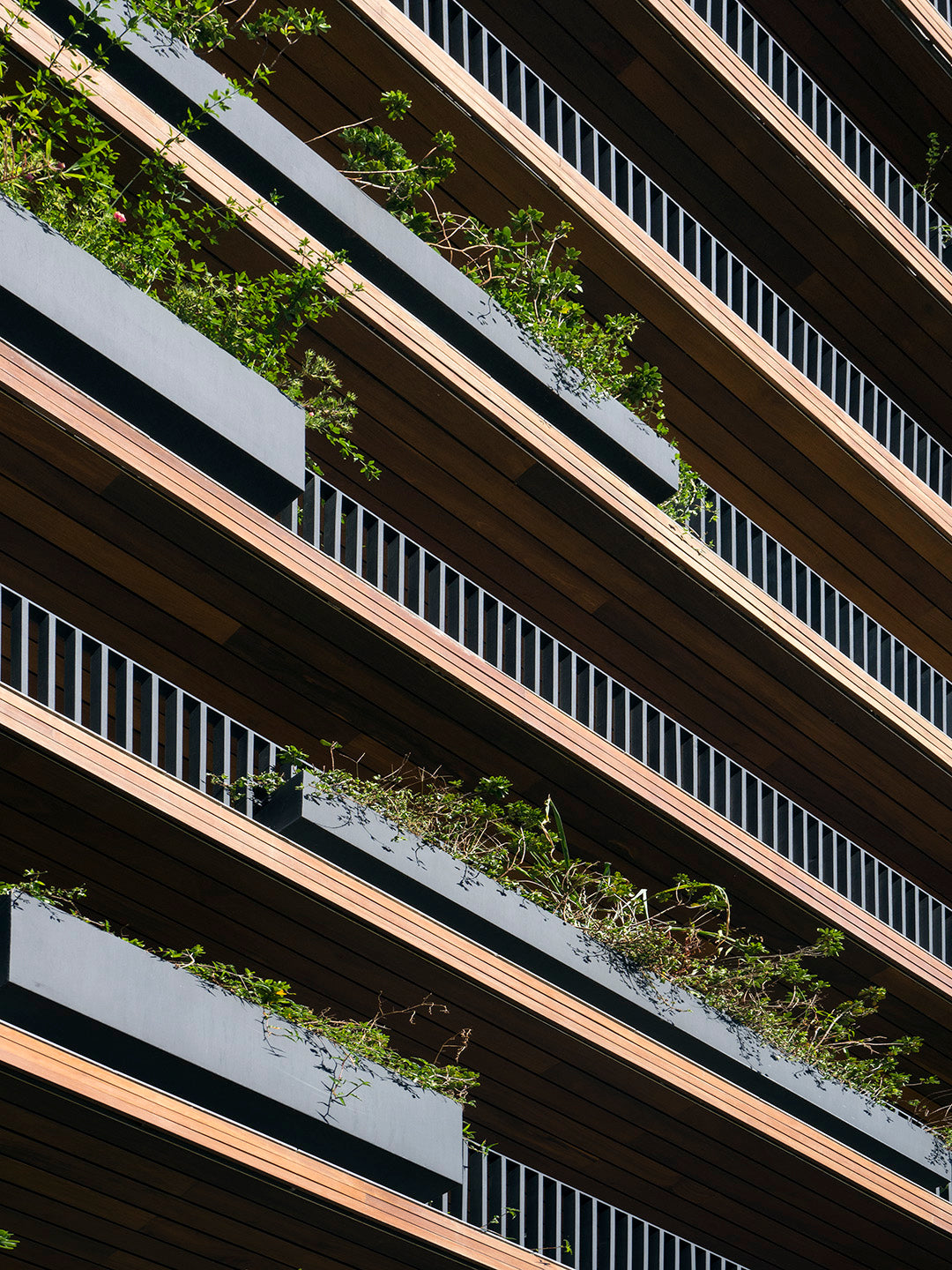

Edificio La Petite Afrique in Monte Carlo was completed in 2016. The modern structure is perfectly at ease among the corbels, friezes, and French doors of the Bauz Arts Monoco district. (Photo: Fernando Guerra)

The straight lines, his love for white walls, his 'Less is More' approach to architecture, and the inspiration was taken from Brazilian tradition and time-honored materials could lead one to think that Isay was simply the new embodiment of Brazilian modernism. But he is much more than that.

He would have struggled with the rules, the do's and don’ts, and the purity of the modern movement. Having to choose between what’s right and wrong certainly has no bearing on the shape of his work. Nothing to fear, nothing to doubt—Isay prefers a rich mix over homogeneity. Although free of the style straitjacket, Isay faced a market that lacked an appetite for good architecture during his beginnings. He graduated in the 1970s when Brazilian architecture was suffering a long hibernation after the inauguration of Brasilia, the modernist capital designed by Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer.

Weinfeld's Edificio Azul was also finished in 2016. The Sāo Paulo structure is divided into three mixed-use structures that attract good views, ventilation, and light. (Photo: Fernando Guerra)

In less than a decade between the 1940s and 1950s, local modernism went from avant-garde for the few to part of the establishment. When Brasilia was commissioned, the new architecture was taken to the summit. Neither Le Corbusier nor his Bauhaus contemporaries could have dreamed of designing an entire capital under the rules of the new modern movement. But its arrival as the official signature of power took its toll.

The fall was fast: Brasilia, with its collection of original buildings and an urban plan that aged badly, was both the peak and the decay of architecture’s power in the country. Brasilia brought financial chaos and inflation with it; the folly of building a new capital in a distant, remote area in just three years compromised both public and private investments in construction. Social and economic upheaval led to a military dictatorship, where free architects were not particularly in favor. Private and public competitions became rare endeavors.

Antiquário Kesley Caliguere in Sāo Paulo is a gallery that is also a house. Built-in 2007, the monolithic neutral colors of every surface highlight the antiques in this domestic art and design gallery. (Photo: Nelson Kon)

Brazilian architecture, once the prized asset of the nation’s culture became nearly invisible for decades among international publications. Today’s classics, such as Niemeyer’s Copan Building or Lina Bo Bardi’s SESC Pompeia, were not celebrated outside of Brazil for far too long.

Many great architects found new retreats during the drought: private homes for relatives and friends and public works for the politically well-connected few. Isay didn’t delve much into the latter, but the former became the first domain where he mastered his language.

Edificio La Petite Afrique balconies are fringed with lush paintings and palms that bring the outdoors inside. This has been a design element that continues to shine in Weinfeld's approach to living. (Photo: Fernando Guerra)

Isay’s love for details made him stand out among his peers. In a country where too many architects were taught to be artists and where the government was a primary client, the demand for finishings, quality control, and usability was lower than it should have been. Isay challenged that standard. “I hate beautiful architecture that’s nice just to look at, but impossible to stay in and enjoy,” he has said. “Comfort is mandatory. It’s like with food; aesthetics are important, but it must be delicious!” He developed his love of designing furniture and the interiors of his works as one simultaneous endeavor: “An interior is not a minor, less important work. Quite the opposite. I love work that can be fully developed, from exterior to interior and furniture.”

Read the full essay in our book, Isay Weinfeld - An Architect from Brazil