Beauty and Brutalism, The Life of Bertrand Goldberg

The legacy of a Chicago icon and pioneer of urban experiments

A pioneer of Midwestern architecture, Chicago-born Bertrand Goldberg redefined the Windy City’s skyline with his Marina City skyscrapers. The lessons learned during his time studying with, and working for, the legendary modernist Mies van der Rohe became a formative part of his architectural character. Allowing form and function to learn from one another, Goldberg moved fluently across a diverse range of scales and projects.

Goldberg worked steadily throughout his career to upend residential and institutional design conventions. Born on July 17, 1913, today marks the 108th anniversary of the iconic designer whose service to architecture is showcased in The Tale of Tomorrow. Following wide-ranging training that included studies at the Bauhaus, Goldberg opened his own office in 1937 at the young age of 24—a rare feat even in today’s world. His fledgling design career took an unexpected detour during the Second World War. During this period, he spent his days developing portable medical labs and gun crates for the government. He then partnered with Leland Atwood until the 1950s, when he went on to found Bertrand Goldberg Associates. His work initially focused on small-scale and intimate residential, industrial, and commercial projects. These early and highly personal works found unique and innovative solutions to individual spatial needs. He completed his last single-family home in the 1950s and soon moved on to projects with larger scopes.

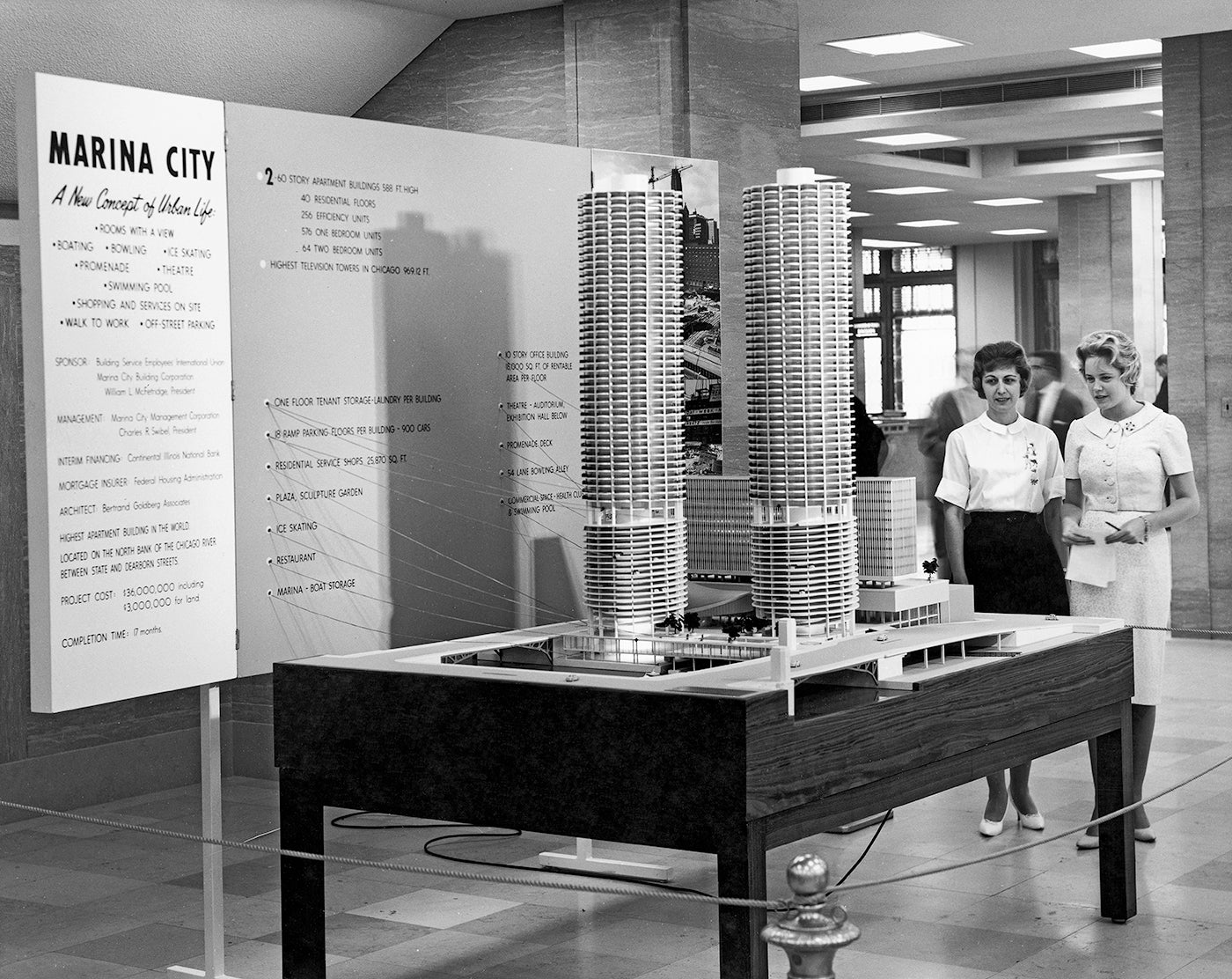

Completed in 1967, Marina City is often regarded as a 'city within a city.' Before downtown Chicago became a trendy neighborhood, Goldberg was one of the earliest pioneers who wanted to bring a new lease of life into the then crumbling area. Now a landmark and highly-sought after residential tower, this skyscraper is often regarded as one of the city's most iconic design. (Photo: Ryerson and Burnham Archives, The Tale of Tomorrow)

Following the success of those first commissions, Goldberg set his sights higher and landed the Marina City development in 1959. This project was a seminal project for both his career and the city of Chicago. This twin skyscraper project saw him achieve significant breakthroughs in material and structural engineering solutions. The high-rise mixed-use complex was completed in 1967, yet endures as one of the most recognizable landmarks along the Chicago River. Several large-scale commissions followed, ranging from residential projects to educational and health care facilities. Each new building produced an equally inventive formal agenda. Goldberg’s practice grew steadily throughout the 1960s and 1970s and soon led to the consolidation of its engineering needs in-house. Goldberg continued working up until he died in 1997. The handsome Wright College in Chicago stands as his last major completed structure.

The Marina City development is as synonymous with Chicago as its tallest building, the Sears Tower. When Goldberg secured the commission, urban centers across the United States were in a state of upheaval. The rise of suburbia following World War II made city life undesirable. The mass exodus to the suburbs and their adjacent office parks left urban cores across the country in various states of abandonment. Goldberg refused to turn his back on the city and instead conceived a design that would reignite the desire to live and work downtown. The mixed-use, multi-building complex includes the iconic 65-story twin towers prominently located on the bank of the Chicago River, right in the heart of downtown.

The corn cob-shaped residential towers are divided into 40 floors of apartments with 20 levels of parking below. Each apartment features curved private balconies and generous glazing to maximize views and encourage connections with the urban surroundings. The pie-shaped layout of the cylindrical towers flares gently outward. Full-scale mockups of a typical apartment unit and the office building were created before construction commenced, allowing the architect and other stakeholders to experience and adapt the design. The slender towers rise from the main plaza in a compelling blend of structure and sculpture. 3,500 prospective tenants applied before either tower was completed. The first was finished in 1962, and the second followed a few months later. Together, they offer 900 apartment units and a range of commercial real estate options. Envisioned as a city within a city, the complex also encompassed a 16-story office building, theaters, restaurants, bowling alleys, pools, an ice-skating rink, and a fully operational marina.

Curved balconies connect Marina City residents to the city beyond. Emanating from a central core, the towers were constructed almost simultaneously. (Photo: Ryerson and Burnham Archives, The Tale of Tomorrow)

Innovative in its design and structural solutions, the project represents the first major use of slip-form construction. Now common in high-rise construction, this process entails pouring concrete into a continuously moving form. When completed, the buildings were the tallest apartment buildings and the tallest reinforced concrete buildings in the world. Initially funded by the Building Maintenance Engineers Union, the project was intended to be a 24/7 complex. As Goldberg argued, “We can no longer subsidize the kind of planning that enjoys only the single-use of our expensive city utilities. In our ’cities within cities, we shall turn our streets up into the air and stack the daytime and nighttime use of our land.” Not one to mince words, he achieved this very goal with grace and vision.

While still intact, the ownership and occupancy of the project have shifted. The once-rentable apartments sold as condominiums and the commercial real estate were transformed into hotel and entertainment venues. A restaurant replaced the beloved ice-skating rink. As the city continues to rise around it, the complex’s panoramic views have gradually been obscured across its lower levels. Despite being well-loved throughout the city and beyond, Marina City has yet to be designated landmarked and protected accordingly. During an era of ‘white flight’ from many of American’s most prominent city centers, Goldberg defied this impulse and presented an alternative way of living for Chicagoans. Although not all can see beauty in his work, this iconic architect stayed true to his principles and ideals, and thus forever ingrained himself in the design fabric of this illustrious city.

Discover the architects and ambitious projects that brought utopian ideals to a mid-century world through The Tale of Tomorrow.