Chef Merlin Labron-Johnson On Minimizing Food Miles

Having earned his first Michelin star at 24, he left London to lead a localized food revolution of his own in the countryside

The elongated supply chains that have come to define the era of globalization have been put under the microscope during the pandemic stretching to the furthest corners of the planet. The fragile system we’ve come to adopt has shown how quickly economies and livelihoods can evaporate. The integrity over food supply chains is nothing revolutionary, but seemingly more relevant than ever. While a pandemic has added a new perspective, chefs championing this change in the wind like Merlin Labron-Johnson presents an alternative.

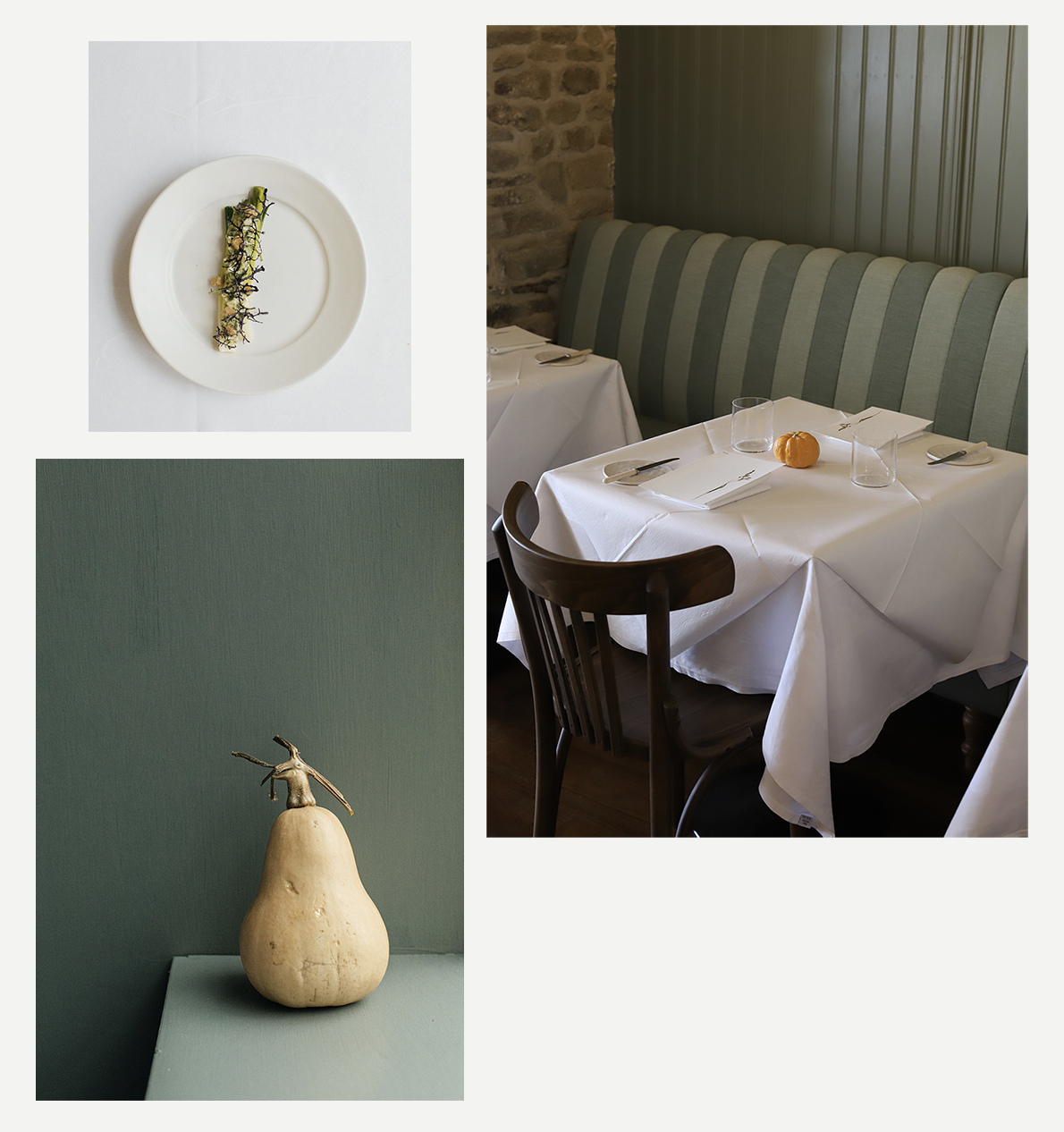

Osip is a small farm-to-table restaurant in the West Country that has embedded itself with local farmers and producers, taking a tailored approach to source ingredients doing the least damage to the environment. (Photo: Maureen M. Evans)

The rural and rustic British countryside of Devon defined chef Merlin’s childhood and taught him about the importance of locality. As a teenager he struck a deal with his school’s chef, often cooking the entirety of his school’s lunch by himself in return for complimentary meals. A mixture of boredom and hunger originally spun the idea. “I certainly hadn't thought much about career options at that age,” he recalls, but it opened a pandora’s box into the addictive “act of cooking for and with other people.”

Despite school cooking anecdotes, the culinary world as a career possibility didn’t dawn on him until later. Next door to the school was Ashburton Cookery School, where Merlin found a job as a chef’s assistant before moving to Simon Hulstone’s The Elephant. From there he ventured abroad for six years in Michelin-starred restaurants in Switzerland, France, and Belgium, before returning to the United Kingdom to open Portland in London. Within nine months, at 24 years old, he was awarded a Michelin star. Over the years this evolved into Clipstone, as he became a staple part of London’s culinary map. But then there was a sudden change to leave the capital behind and return to the West Country.

The concept of Osip is to bridge farm-to-table cooking with innovative refined dining, in a fuss-free fashion removed from the demands of cosmopolitan life. (Photo: Maureen M. Evans both on the left, Jessica Wang top right)

“I grew up in the countryside and learned to cook abroad, working in remote locations surrounded by nature and farming,” he explains. For various reasons, his vision of what a restaurant should be felt compromised in a big city. Toward the end of 2019, Osip was launched in Burton, the second smallest town in the UK. “Here my plan is to create something that feels like a very pure expression of a time and place in Somerset, without wanting to sound too cheesy! That is to say, when you come to my restaurant, you can taste and feel where you are with everything you eat and drink,” he says. Sometimes you have to create something new and completely out of the way for it to be special.

This culinary mission in many ways marks a return to the organic and sustainable environment he grew up around. With the changing future of food, a topic set to define the next generation, working in more sustainable and localized ways will become the norm. “As a restaurant, we want to prove to ourselves and our community that you can serve great food whilst taking care of the environment by using entirely local ingredients, planting our own food, minimizing food miles, recycling our food waste, omitting the use of plastics, upcycling our cardboard and supporting small independent producers who work in a responsible way,” he explains. Plus using surrounding green spaces for growing vegetation. Of course, this isn’t revolutionary, they “don’t want to make too big a song and dance about it but we are hoping to become better at what we do and in time, a good example of a 'sustainable' restaurant.”

Since relocating back to the UK, he has managed to devote time to charitable projects. In London, he was a regular at Massimo Bottura's community kitchen Refettorio Felix in Earl’s Court, held countless fundraisers for Help Refugees, and holds an executive chef role at The Conduit, a club committed to creating a positive social impact. (Photo: Jessica Wang)

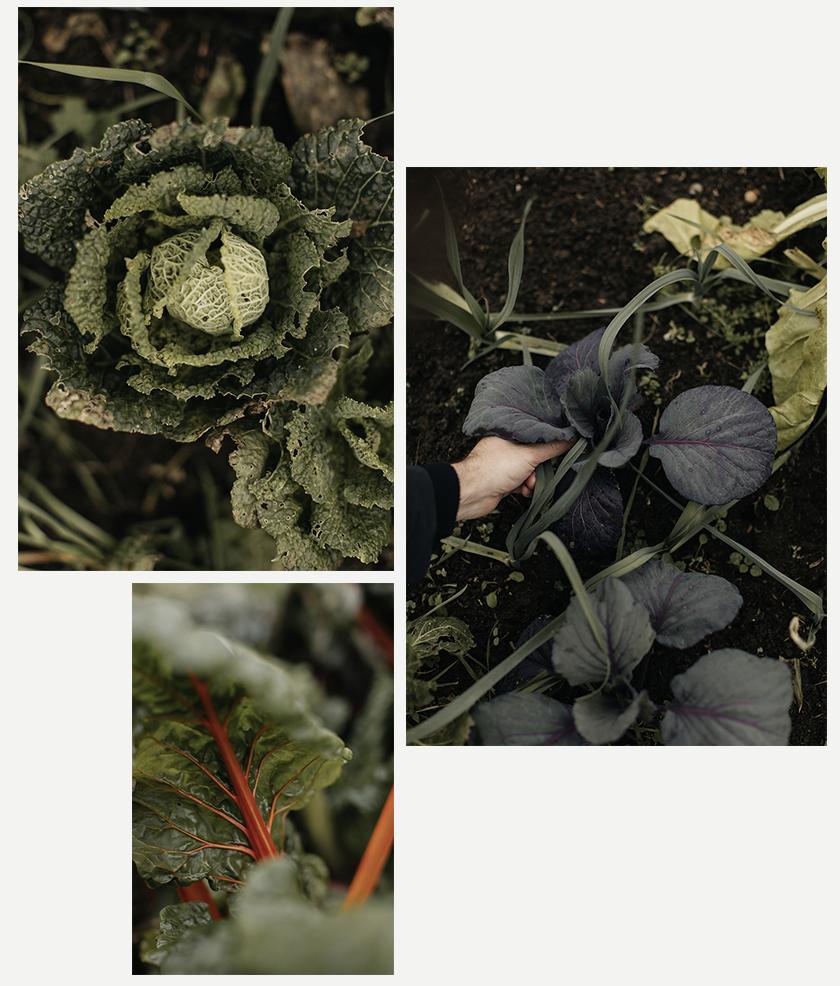

This is not the future, it is happening now, the industry is changing like a bird moving on from a tree. “The most important thing that we are learning and practicing is nurturing and looking after the soil and nature so that it will, in turn, look after us,” he explains. It seems like a fairly obvious and straightforward principle of agriculture and husbandry!

During his time in Belgium, he worked at In de Wulf for two years in the remote countryside. This place embodied the philosophy of farm-to-table, an idea set to shape his career later as the focus turned on the provisional supply-chain of food and consumer. This was his last stint abroad before changing scenery. “When I moved to London I felt liberated, taking pleasure in being able to procure produce from further afield. I experimented with ingredients from the Mediterranean and even Asia, sometimes. I eventually got bored and returned to my more instinctive cooking.” This taught him a lesson. He realized that “when you cook with whatever you like, it's too easy, you become complacent and there's less need to be creative. When you are restricted to working with only local, seasonal, or homegrown ingredients, it can be challenging, especially in winter. This forces you to think outside the box and pushes you to create food with a stronger identity, which is a very good thing.”

For environmental reasons, Osip had made the decision to veer away from using red meat. Chef Merlin personally sourced and collaborated with all the local farmers in its supply chain, ensuring locality across all levels of the supply chain. (Photo: Maureen M. Evans)

Osip was four months into its journey when Europe was gripped by COVID-19, forcing it to close during the lockdown. Like many other establishments, the language of adaptation was learned overnight and new models for survival arose, often ones never considered before. With the light now appearing at the end of the tunnel, there is a wonder what restaurant culture might look like beyond this pandemic. Looking toward the future, chef Merlin says, “this will probably push us to create an even more unique offering to justify the price and we may end up with a completely different restaurant to when we set out.” Hopefully a better one he elaborates, “I think people will dine out less and when they do, it should be more special. I'm going to throw everything I've got at it and hope that we survive.”

Trying to take a positive outlook in a pandemic, he is looking at this as a healthy exercise to undertake—although one that wasn’t wished for. As is so often the case in times of socioeconomic quandary, there is an opportunity for cultural and political change, if desired. Will the present turmoil lead to a change in the food supply chain and create a more localized revolution? Maybe, maybe not.

Everything is sourced and packaged ethnically, their focus is on focus on organic and biodynamic vegetables over red meat (Photo: Maureen M. Evans)

Predictions and proposals are being thrown far and wide. But he can see people latching onto the idea of 'supporting their local,' which is great, but this idea is often presented in a privileged society that has the ability to choose from where to buy. Supermarkets will almost always be cheaper, but we have to “find ways of farming on an industrial level without causing harm to the environment,” he argues. There’s no denying that producing good, nutritious food using responsible farming methods and farmers are more expensive, but a fair price warrants the hardship. There needs to be a way to make food supply more sustainable and accessible to all parts of society.

They work with a small but perfectly formed group of local farmers, growers, hunters, and gatherers to put together daily changing menus that reflect the very best of Somerset and its environs at any given moment. (Photo: Maureen M. Evans)

That said, he does “think that in the pandemic has brought the consumer closer to the producer and made them put more value on the people that produce their food. A step in the right direction for sure!” Ultimately, this could be a moment in history to dismantle unsustainable supply chains and relocalize, if societies want it to be.

Discover a world of plating, global food cultures, and sustainable innovations through a selection of gestalten food and beverages titles.