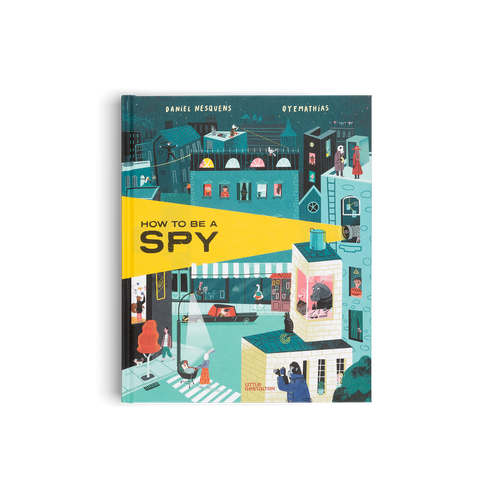

01/2020 architecture & interior

In 1937 during a trucking delivery to Hoboken, New Jersey, Malcom Purcell McLean was forced to wait for hours in his vehicle, watching longshoremen loading and unloading goods into holds. Experiencing a moment of frustration rather than a Sir Isaac Newton breakthrough in science, McLean left in wrath and thought of the whole ordeal on his journey back and later that night in his dreams. When he woke up the next day, he couldn’t possibly have imagined how much his idea of building a freight container would transform the world.

Dubbed the ‘Father of Containerization,’ McLean evolved from his humble beginnings as a North Carolina farmer. Born in 1913, he grew up weighed down by the obstacles of the Great Depression but was determined for more. The entrepreneur spent time as a petrol pump attendant, and later a truck driver who would go on to own the ‘McLean Trucking Co.’ fleet, the second-largest trucking company in the USA with 1770 vehicles at one moment in time. Capitalizing on the changing economic landscape, McLean was a byproduct of the ‘American Dream’ and the social mobility that defined that era.

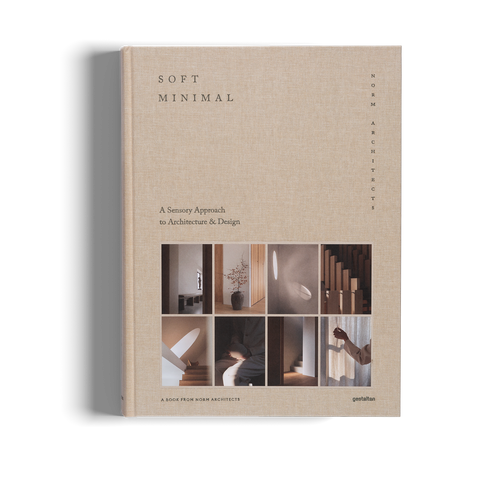

Container Atlas is the eagerly anticipated follow-up to our original bestseller that charts how this movement has evolved into an essential part of today’s architectural vocabulary. (Photo: Danny Bright)

His trucking career inspired him to fundamentally alter the centuries-old shipping industry, a sector that had long decided that it had no incentive to change. Freight containers were a new system that allowed ships to reduce docking time from days to a couple of hours—revolutionizing the movement of goods around the world. He created transparency in the industry and enabled movement in bundles. While his invention disrupted the lucrative packing goods industry and its employees, it opened the door to mass-movement and globalization.

McLean died in 2001, he lived long enough to watch containers metamorphose into a mastermind of movement, but not yet architecture or design. Although Japanese Metabolists and the British group Archigram of the 1970s were spurred by McLean’s creation, container architecture didn’t fully arise until the new millennium.

The second phase of this movement was documented in detail by Professor Han Slawik in Container Atlas a decade ago. As the approach continues to evolve along with the design identity and possibilities, the style is going beyond the realm of commercial and breaking into the art world and esteem design. To celebrate this evolution, a revised edition has been released to commemorate the occasion. From Biennale art pieces to zigzag formations amongst sacred mountains, we delve into four epitomes taking this specialty to new heights.

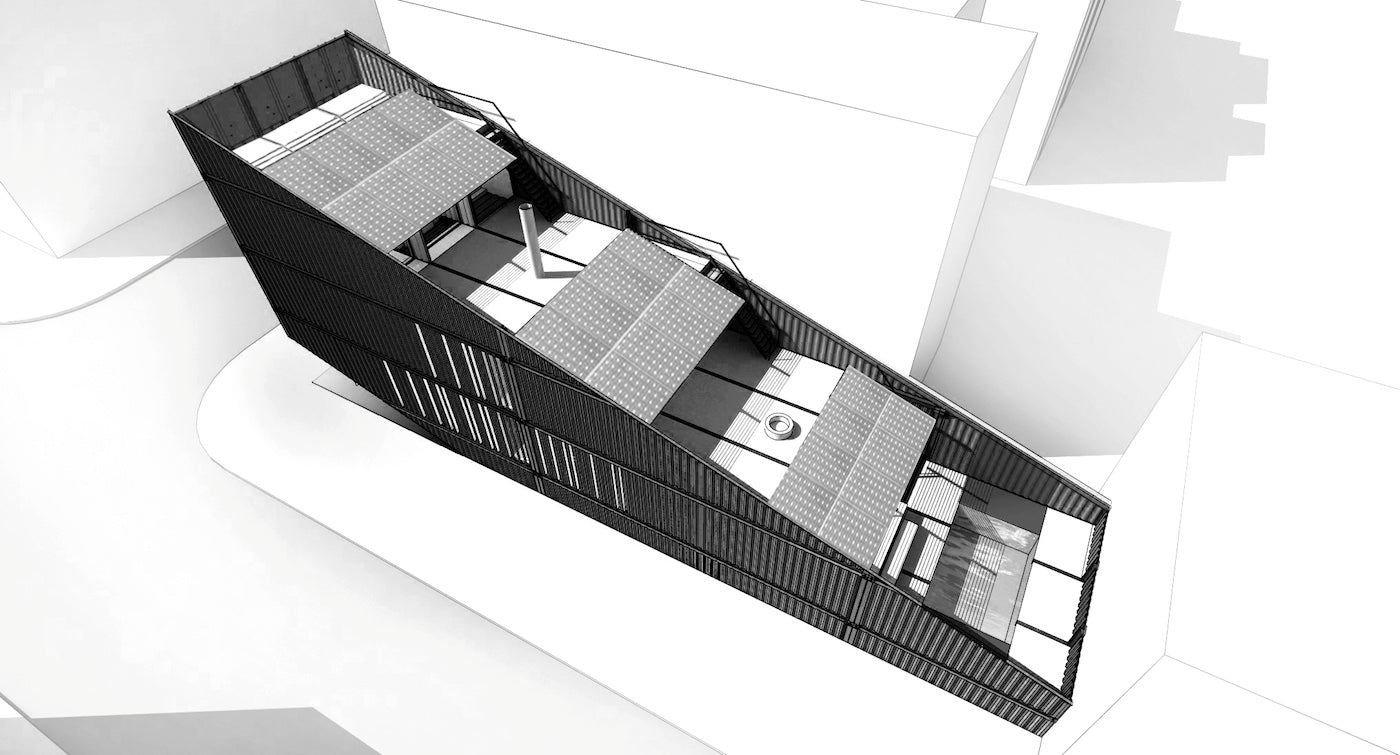

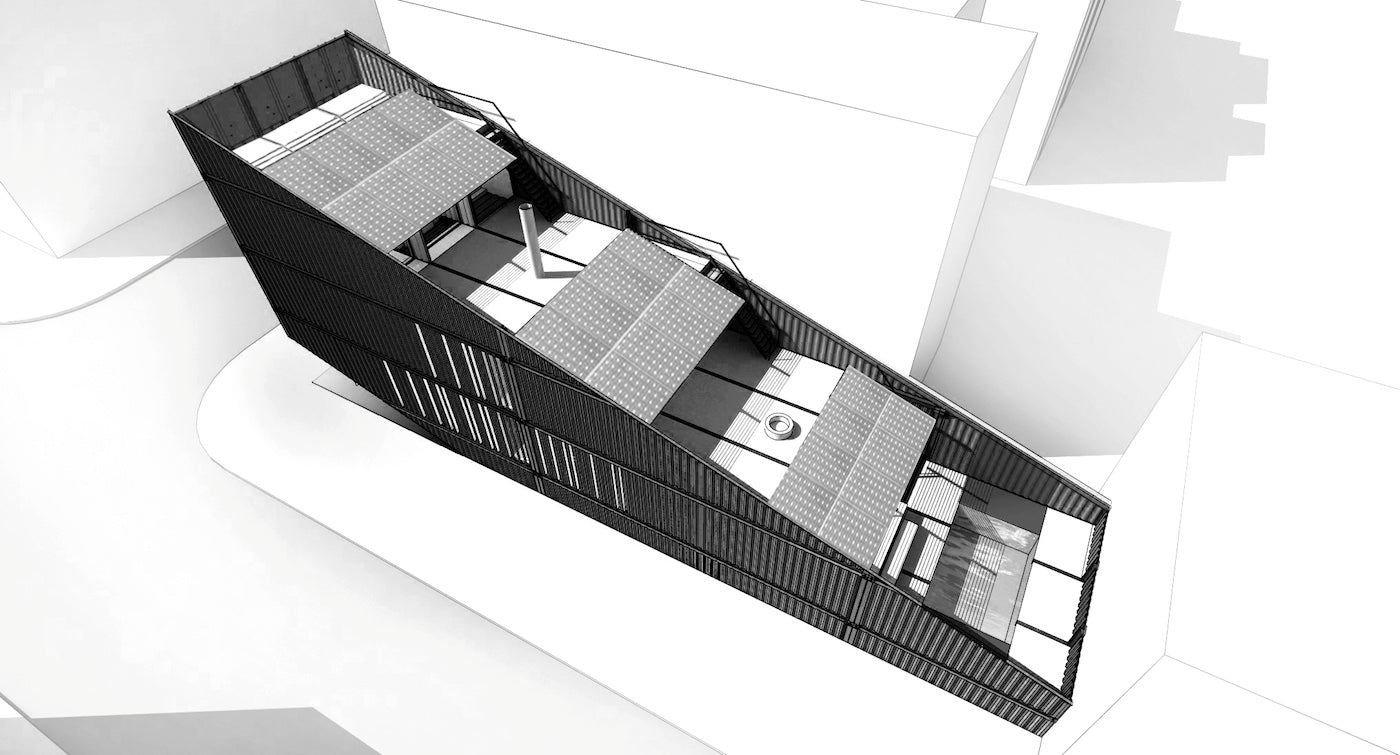

The diagonal volume built from 21 stacked freight containers. The diagonally cut containers on the ground floor make way for a ramp that leads to the cellar and garage. (Photo: Danny Bright)

Carroll House by LOT-EK, New York

On a typical Brooklyn lot, New York and Naples practice LOT-EK has constructed a less-than-typical family residence. Shooting out of the pavement like a monolithic diagonal beam, Carroll House is constructed from 21 stacked containers that are cut along the top and bottom. The result is a 232 square meter (2,500 square foot) diagonal volume where three of the four levels have a private outdoor space at the rear, shielded from public view thanks to the strategic cut of the container walls. The outdoor spaces are framed by large glass sliding doors, creating continuity between inside and out.

The containers are stacked to create ample outdoor space along the rear of the building. The kitchen, dining, and

living spaces are found on the first floor. (Photo: Blueprint of Carroll House by LOT-EK)

A downhill ramp at the front of the building offers access to the garage on the lower level, where the cellar is also located. The kitchen, dining, and living rooms are situated on the first floor, as well as a media room with a projector and bleacher-style seating. One floor up is a level dedicated to children, where two bedrooms and a play area are each carved from a container. The main bedroom and en-suite is tucked away on the top floor.

The containers that point skywards fill the home with natural light. The architects referred to Joshua Tree as “the perfect match” for this particular building form. (Photo: Render by Whitaker Studio)

Joshua Tree Residence by Whitaker Studio, California

Planned for completion this year, the Joshua Tree Residence almost did not happen. The structure was originally conceptualized a decade ago prior to an advertising agency in Germany, which backed out before construction began. A private client in Los Angeles asked Whitaker Studio if the idea could be revisited as a holiday home on a striking plot of land in the Mojave Desert, outside the small town of Joshua Tree. This region of southern California has long been fertile ground for architectural experimentation, from Andrea Zittel’s sleeping pods to Albert Frey’s modernist residences in nearby Palm Springs.

Interior renders showing bedrooms branching out from the entrance hall. Exterior renders showing the home against the dramatic Californian landscape. (Photo: Render by Whitaker Studio)

Inspired by the growth of crystals in a laboratory, the structure’s effect is achieved through 19 white shipping containers welded together on site. The placement of each of these is defined by the surrounding landscape: the kitchen is oriented to catch the morning sun, while more private spaces like the en-suite bathrooms face a rocky slope. The composition was designed with a dramatic entrance in mind. According to the architects, when all internal doors are open, you can stand in the middle and look out at the radiating spokes on all sides.

The camp is seen in context with its natural surroundings. The site is color-coded based on function. (Photo: Noah Sheldon)

Qiyun Mountain Camp by LOT-EK, China

More than pristine landscapes, China’s Qiyun Mountain is one of the four sacred mountains of Taoism and believed to be the place of origin of the yin-yang symbol. Situated amid the verdant peaks, Qiyun Mountain Camp is an adventure and extreme sports park—the largest of its kind in China. The base units are made from shipping containers cut on a bias, which are joined, mirrored, and tilted together forming a dynamic set of structures. The clusters zigzag, project on a diagonal axis and, at the focal point of the park, emanate outwards in a star-shaped volume.

Containers on an angle allow visitors to explore the landscape from different vantage points. (Photo: Noah Sheldon)

The sprawling complex is divided up into several different clusters, each color-coded to help orientate guests. It contains shops, cafes, service areas, pergolas, and observation decks to take in the landscapes. In the yellow and blue area, a restaurant plaza is situated on a hill overlooking the river below and forming an outdoor amphitheater. Another container, hoisted up in a diagonal, is a launch platform for a zip line. Near the lake, a cluster of modular units forms changing areas, cafes, and storage for kayaks. The buildings encourage flow towards the lake, where a floating pier stretches into the water.

The boxes were stacked on both sides and end to create a variety of interiors. Not just fine art exhibition spaces, the containers supported a variety of events. (Photo: Bureau A)

Biennale of Independent Spaces for Art by Bureau A, Geneva

Swiss architecture firm Bureau A, made up of Leopold Banchini Architects and Daniel Zamarbide practice, playfully mimics one of the wonders of the world with Steelhenge, a cluster of 50 disused shipping containers arranged in a circular formation. Not quite as mysterious in construction as its English counterpart, the cluster of containers were brought in to create a weekend-long open-air venue in Geneva, as part of the first biennale for independent art spaces in the city.

The circle of 48 containers formed a steel Stonehenge and a democratic cultural milieu. (Photo: Bureau A)

To the architects, Stonehenge was a particularly interesting reference for the pagan rituals it is associated with—which, in turn, was associated with Geneva’s alternative and squat culture. The container itself—readily available and easily reused—was a viable choice given the restricted budget and that the pavilion would only be in use for a long weekend. The structure in its entirety was built within a single day with the help of a crane and concrete blocks to stabilize the containers. Painted blue and ranged in a radiant circle, the containers established a striking contrast with the chalky red dirt floor of the public plaza.

Find out more about Container Atlas.