Francesca Gavin on the History of Collage Vol2

After exploring the evolution of collage until the postwar era, curator and writer Francesca Gavin follows seven decades of artistic progression of the medium until the present day

Robert Rauschenberg adapted collage to the industrial machine age. In 1961, MoMA put on an exhibition, The Art of Assemblage, showing how the medium was beginning to define the age. William C. Seitz saw collage as an extension of human experience. He wrote in the catalogue, "The placement, juxtaposition, and removal of objects within the space immediately accessible to exploration by eye and hand is an activity with which every person’s life is filled, virtually from birth until death." Seeing was a form of collage making.

From 1958 and throughout the 1960s, the boundaries of pop culture and high art became blurred. Pop art was an anti-hierarchical approach that reflected the era of supermarkets and media saturation. Eduardo Paolozzi had been creating collage works in the United Kingdom since the mid-1940s, but only gained recognition in the coming decades. He had collected pictures from popular magazines since he was a child and saw Surrealist collages and Duchamp’s magazine-image-covered studio walls in Paris in 1947. He originally drew from his Italian heritage, upsetting fascist imagery by combining images of Roman sculpture with industrial machines and scrawled colored pencils. His Bunk series from 1947 to 1952 was printed as a facsimile in 1972. This vibrant set of collages combines pulp magazine pinups, low culture, and ads. He later called the series "readymade metaphors." For Paolozzi, collage as a word was inadequate for the energy of the medium. "The concept should include damage, erase, destroy, deface, and transform," he observed.

Paolozzi’s contemporaries, Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake, were also drawn to similar inspirations and references, parodying contemporary advertising and creating visual love letters to their icons. Mass media imagery became "a raw material like charcoal or paint," as Lisa Tickner wrote in London’s New Scene: Art & Culture in the 1960s. Pauline Boty was a forgotten central artist of the pop-art scene, who sadly died young. The iconic Ken Russell’s documentary Pop Goes the Easel starts and finishes with Boty’s collaged studio wall. Her found materials ranged from postcards of old masters to Hollywood idols, and fed into her paintings combining magazine-like visual effect, flatness, graphic symbols, and similar content.

French theorist, Guy Debord, was engaged with the same media landscape of the postwar era. His aim, along with the movements he helped found, Lettrism and situationism, was to disrupt the propaganda of the spectacle of the media machine that had ingrained itself in everyday life. He demonstrated how meaningful life was not possible under capitalist image control. "The spectacle has spread itself to the point where it now permeates all reality," Debord wrote. Collage was not just a way to bring awareness but detournement, a method to disorientate and resist.

Angela Davis (with pink) by Peter Horvath 76.2 × 91.4 cm, 2018. (Work: Peter Horvath, The Age of Collage 3)

Although he had a distrust of art, many artists were fundamentally influenced by his ideas about cultural consumption. The radical King Mob group in Britain, which Malcolm McLaren was connected to, was affected by his approach so much that they included situationist slogans in their visual output. The reworking of images, text, and found material became the adopted method of the mid-century avant-garde. William Burroughs collaborated with artist Brion Gysin on cut-ups from 1959, juxtaposing newspaper clippings, original text, and photographs. The chaotic results were, to Burroughs, a mirror of life. "Cut-ups make explicit a psychosensory process that is going on all the time anyway," he said. Cuts reflect the multiplicity of human awareness and altered and exposed ideologies. While the mainstream media praised coherence, Burroughs presented nauseating chaos. "When you cut into the present the future leaks out," he wrote.

His approach, which also involved creative experiments in audio and film, influenced everyone from David Bowie to author Kathy Acker. The West Coast was also adopting collage, in particular sculptural assemblage, as the language of the era. Wallace Berman’s hand press journal Semina ran from 1955 to 1964, featuring the work of Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Alexander Trocchi, Llyn Foulkes, and Jean Cocteau. Berman’s collaged pieces established the aesthetic of the publication, combining Hebrew and Kabbalistic references, inventory numbers, and the repeated Xeroxed image of a hand-held transistor radio holding different found photographic elements. Semina also printed collage by Bobby Driscoll, Dean Stockwell, and Diane di Prima, a poet who created visual works referencing the I-ching, Kabbalah, alchemy, Zen, Buddhism, and the esoteric. Collage was strongly intertwined with the rising counterculture. Bruce Conner was making a paper collage with wood, glue, and nails, and, from 1954, editing films.

Ed Kienholz later joined by his wife Nancy, used found things to create dirty sculptural objects and immersive environments. Collage was also fundamental as a method for black artists to find a new voice and audience. American artist Romare Bearden made his name in the 1960s with figurative collage street scenes and narrative portraiture with immense success.

Collage appealed to him, in particular, for its accessibility to a black audience, as it provided a contrast to the obtuse nature of abstraction. For Bearden, collage "symbolizes the coming together of tradition and communities." His politically and socially conscious work reflected his strong involvement in the civil rights movement. He used glossy magazine imagery to incorporate the reality of existence and emphasize the progress of a society in flux. Visually, his approach to the material was almost painterly, using images as blocks of color, peppered with moments of found faces to ground the work in the real. The result was almost sociopolitical pop.

Black artists working and exhibiting in Los Angeles between 1960 and 1980 were looking to their environment for detritus to transform into sculptural artwork. Betye Saar started creating assemblages in the late 1960s, using discarded consumer objects that often had racist connotations, usually items that touched on cosmic esoteric aesthetics or historical objects from her own experience. Saar recycled the derogatory into objects of resistance. "I started collecting those images in the 1960s because I’m just a seeker and a hunter; finding things to use and recycle. Going through stacks of postcards and other printed images, I became aware of all these derogatory images of black people," she recalls. These included Mammy figures, Uncle Toms, and blackface advertisements. "I became an artist who wanted to influence people to see these images differently." Aunt Jemima went from a slave or a subjugated working person into a heroine.

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Leonardo Da Vinci by Milen Till. 70 × 90 cm 2017. (Work: Milen Till, The Age of Collage 3)

Saar exhibited at the Brockman Gallery in West Los Angeles, which was created in 1967 with a focus on artists of color. Many of these names were working with collage. Alonzo Davis created mixed media collage on canvas, while Marie Johnson Calloway made collage figure cutouts. David Hammons’ practice was strongly intertwined with the collage approach. He incorporated found objects, from chicken bones to hair and paper ephemera, into his pieces. The dirt and detritus of life were fundamental, as was the context in which he showed his work. "I like doing stuff better on the streets because the art becomes just one of the objects that’s in the path of your everyday existence," he explained. "It’s what you move through, and it doesn’t have any seniority over anything else."

Collage also became a central language for feminist artists, starting in the 1970s. Mary Beth Edelson, for example, is an artist who, between 1972 and 2011, created a mammoth installation of 146 collages exploring the representation of women through time. The hybrid cut-up characters she created connect to her wider interests in goddess worship, nature, and the history of humanity, but also the role of women artists in history. Her collage has political as well as artistic intentions. She once described her aim as "working toward social change in an asymmetrical culture, making the political aspects of identity and the female body visible." Miriam Schapiro’s collages intentionally reflect the history of the decorative craft, repositioning hearts and fans filled with flowers and decorative motifs as emotional, feminist objects. It is almost a return to the history of the decoupage, from a modern perspective.

Feminist meets punk in the work of Linder Sterling. Her collages first gained attention on the cover of The Buzzcocks single Orgasm Addict in 1977. The acid-yellow seven-inch record depicts a muscular, naked female torso with an Argos catalogue iron for a head and two toothy smiles for nipples. Linder was one of the first artists to use porn as a material, strongly influenced by second-wave feminism and John Berger, whom she had read while studying graphic design in Manchester in the United Kingdom. Her work feels almost violent. Images of bodies are sliced, diced, and reconfigured. Faces are often covered by anything from flowers and domestic appliances to a 1970s hi-fi. The homespun nature of collage has perfect synergy with the provocative lo-fi concept of punk.

Artists such as Jamie Reid and Peter Kunard combine the graphic approach of collage with the rough rebelliousness of punk. Barbara Kruger’s work was not directly part of the punk scene, but it had an equally striking tabloidesque take on appropriation. Kruger, alongside artists such as Richard Prince and Dara Birnbaum, questions how images consolidate dubious ideas around gender, politics, and meaning. These conceptual artists destabilized the idea of image ownership, highlighting how material thrown into the public realm can be open to criticism. The same approach can also be seen in music, in particular how hip-hop and sampling use the foundation to create new forms. Both continue to be plagued by copyright infringement issues. Over the past two decades, collage has become a central medium in international art. Artists using the technique came from two directions. For some, collage was a way to address history and the archive, coming out of a heritage of creative research that was started by Aby Warburg in the 1930s. Artists such as John Stezaker and John Baldessari used found imagery from Hollywood to make statements on ideology, photography, and truth. Hanne Darboven and Tobias Buche used found material in a more encyclopedic way. Here images were placed in grid-like compositions. These fascinating contrasts of content demonstrated hidden narratives as well as the futility of trying to make sense of a century of printed material.

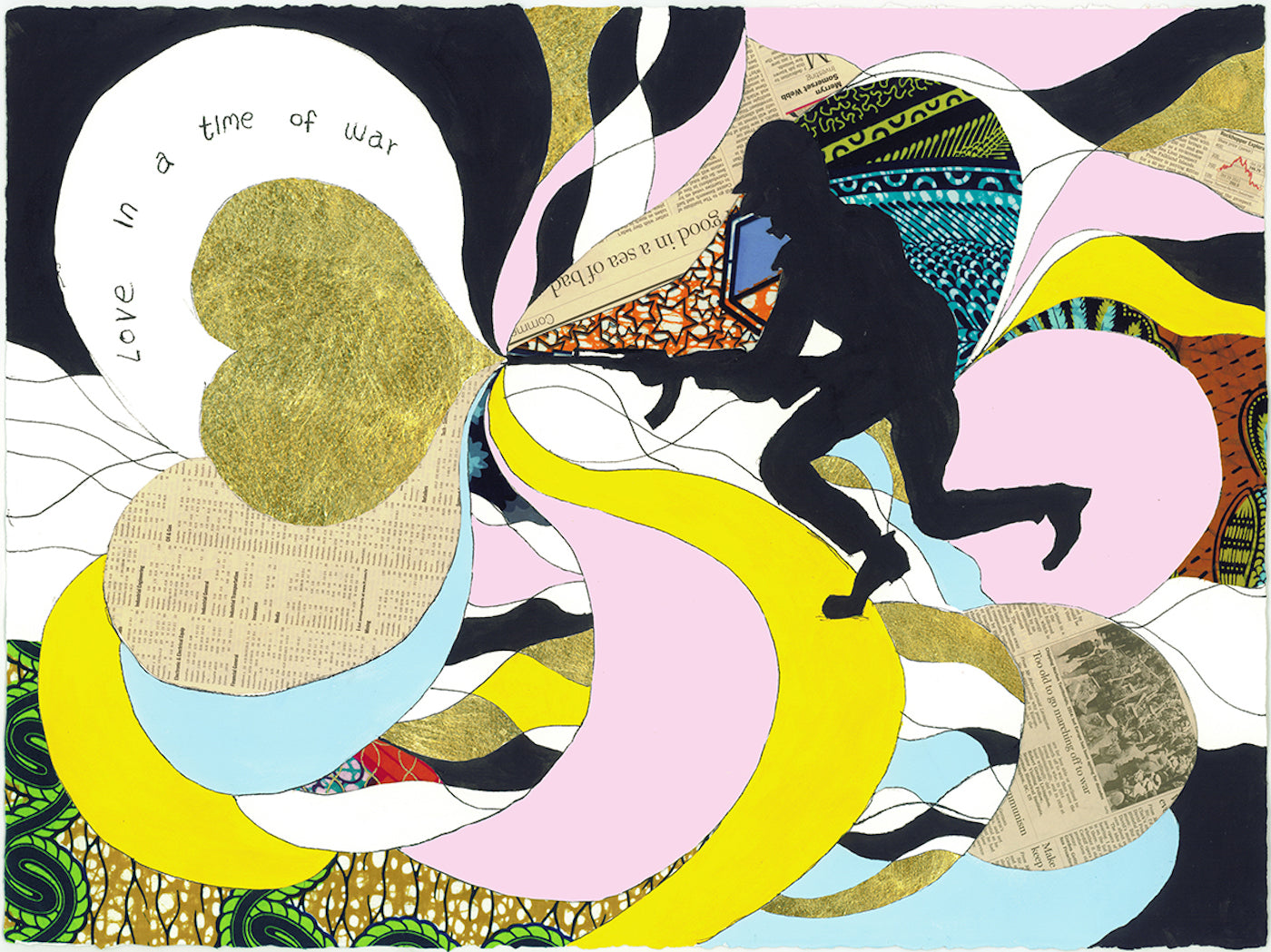

For artists Dash Snow, Isa Genzken, and Thomas Hirschhorn, collage was an expression of violent energy and political critique. Collage became dirtier. The ripping, reusing, and layering of the material was as important as what was depicted. Wangechi Mutu, Ellen Gallagher, and Sonia Boyce also demonstrated how collage was an ideal medium to explore ideas around identity and the depiction of blackness, and to twist the bias of found imagery.

‘S’ PICTURE (Homage to Uglow) Jonathan Yeo. 42 × 59.5 cm 2008. (Work: Jonathan Yeo, The Age of Collage 3)

Photographic material has also been transformed by the digital. The cut itself has become invisible unless the artist deliberately wants to show it. Creating things by hand is an intentional gesture that has brought with it a resistance to the digitization of image consumption, and an awareness of the manipulation of photographic imagery. The function of photographic imagery has completely changed. It is no longer seen as a straight representation of the truth. As artist Martha Rosler notes in her essay Image Simulations, “Any familiarity with photographic history shows that manipulation is integral to photography.” Framing, lighting, filters, lens, post-production, editing, Photoshop, and even staging all have an impact on a printed image, let alone the point of view of those who take and publish a picture.

Images of factories, naked women, and appliances are all adjusted to remove any dirt or 'imperfection.' "Technology is following a cultural imperative rather than vice versa," Rosler notes. Collage has become a methodology to critique source material from within. The internet has led to a huge shift in image access, which has been a direct influence on contemporary collage. The printed image itself is a dying material. Many artists are looking at vintage material, drawing on different print techniques and content, because it says something about the past and has been discarded.

Artist Jonathan Yeo, for example, collects vintage porn magazines to use as tonal material for complex portrait collages. Other artists are using digital media in new ways to create layered compositions. The internet has also become a vital space for the dissemination of collage imagery. Social media, blogs, and websites are the galleries for a new generation of collage artists. The idea of mass culture and media has been expanded. We see more images than ever before, and collage is a way of making sense of that chaos. Artists are using collage to symbolically resist consumption and recreate the world in new ways. The process of addition and removal and combining contrasting elements is not just an artistic process. It is a way of thinking.

Learn more about an art form which is shaping visual communication in ever new and provocative ways through The Age Collage 3.