The Last Dreamers of Modernity

Apartamento magazine’s creative director Nacho Alegre reflects on the legacy of a fellow Catalan

For most of my life, I regarded Ricardo Bofill through an aura of mystery, almost irreality. His public persona, as I saw it in my teenage years, danced between that of a hermit-artist and celebrity. The public and critical opinion of him likewise split between respect and loathing, awe and dismissal. I have photographed the architect, collaborated with his workshop, and even befriended his son; while I would hardly call us close, I have come to a much closer, more nuanced understanding of the man, his work, and the collaborative community.

I’ve always been very attracted to Bofill’s work. Childhood friends of mine in Barcelona lived in the iconic housing complex Walden 7—even to the eyes of a child that building was very different from anything else. It exudes fantasy, and power—it felt new but had about it something primitive, rooted in a very familiar, shared past. The building was placed in what was then a no-man’s-land, protruding from the ground in a former industrial area like a Moorish castle—proud, defying its surroundings. This foreign-seeming, fortress-like volume contrasted with the bustling life that it contained: the village feel, the number of young people—of children running happily around, unwatched, climbing up to the pool on the rooftop. Although the corridors are named after poets, there is also the dark side: the stories of people coming in to jump from the roof to kill themselves, the drugs (Barcelona was suffering through a heroin plague in those years), the hostile surroundings. This contrast somehow only made it more attractive.

When, years later, some of my friends went on to study architecture, I was surprised to see the work of Bofill conspicuously ignored throughout their studies. Their teachers, of an age similar to Bofill—many of them his colleagues and certainly familiar with his work—seemed to pay no attention to him. All this time, Bofill had been working abroad, and very successfully—a defection that perhaps he was made to pay for.

Experimental innovators vs. conceptual innovators. One type of artist will spend their whole life striving for one painting, the other will move on as soon as he’s happy with the idea he was exploring

I met Ricardo Bofill for the first time at his studio. I was sent there by an editor and creative director Felix Burrichter, to shoot for PIN-UP, his architecture and design magazine. I had never been to La Fábrica before. When I arrived, I walked into La Catedral, which is something of a border between the public and private parts of the house. The proportions of the “nave,” its misty light, the roughness of the walls contrasting with the formal furniture—it all presses a religious feeling onto the visitor. Minutes later, I was called to meet Bofill, so I could take his portrait. I met him at the entrance to his office, on the second floor of the “silo building,” a structure of four former cement silos bound together. In this room, the walls had been cleared—it was a clover-shaped space, painted in white, with natural light flooding in through the gothic windows, bouncing off the cashmere carpet. The room was of exquisite elegance, and almost monastic. On one side, there was a small table with two Thonet chairs; on the other, a big drawing table, where the architect works. The person taking me to Bofill called him “Maestro.” We shook hands, and I explained to him what I wanted to do. He knew the magazine and told me he loved the pictures that were taken of Richard Meier; overwhelmed by the setting, I pretended that I had shot them. After a minute of indecisive looking around, I took a picture of an ashtray. I asked Bofill if he smoked. He offered me a cigarette and also lit one for himself. And then he looked at me with the warmest smile and we started taking pictures. For over an hour, I enjoyed his attention while he took me on a tour around the house. Far from being distant, he was happy to tell me anecdotes about the building and the things that we were seeing. When he caught me looking at a Roman bust (which I had thought was an ancient treasure), he explained that it came from the souvenir shop at the Louvre and encouraged me to buy one myself.

Ricardo Bofill stood by his principles and steered his work toward the future. He hoped his legacy and his generation would be on that had a stronger emphasis on community and how we connect as humans. Although his style often failed to get the respect of his architectural peers, his legacy forged a place in the history books because of its ambitious scale and cult following. (Photo: Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura, Ricardo Bofill - Visions of Architecture)

Meeting Bofill may have killed the myth, but it prompted the discovery of another side of the architect’s world. It changed him from an almost fictional character to a real person, and it was then that, through my magazine Apartamento and with my friends from studio Arquitectura-G, I started becoming more deeply interested in him.

Bofill was born on December 5, 1939, in Barcelona. The son of a contractor, in the dullest hours of the Franco regime. As he explains himself, the feeling of being, not in the middle of the world but the outskirts, in a periphery—a Catalonia that was not just physically isolated from the cultural capitals but also far from national, political decision-making—sparked dreams of freedom and faraway lands, and was probably what later inspired his nomadic lifestyle. The importance of the vernacular, it’s engagement with classicism, Bofill’s sense of atemporal elegance—all find their roots in this early period.

There are two types of artists: those who spend all their lives perfecting a language, like, say, Rembrandt, and those who change their language across different periods of their life, say Picasso. The social scientist and theorist of artistic creativity David Galenson, with a different edge, define these two groups as experimental innovators vs. conceptual innovators. One type of artist will spend their whole life striving for one painting, the other will move on as soon as he or she is happy with the idea that was explored. Certainly, Bofill belongs to this second group. To dismiss him for this, however, would mean denying any kind of human perspective. Even if the work of the architectural critic is perhaps to evaluate, to categorize these different periods, it should also delve into the personality underlying, what are, behind the stylistic facade, the constant, career-spanning characteristics of his work.

Walden 7 was imagined as an architectural Rubik’s Cube, with all apartments tessellating but leaving gaps in the core that act as communal space. (Photo: Salva López, Ricardo Bofill - Visions of Architecture)

Far from the grandiloquence of some of his later projects, Bofill’s first, in 1960, was a humble house in Ibiza. Instead of applying his credo to the plot, Bofill studied and applied what he thought useful from the vernacular architecture of the region, adopting traditional forms and incorporating inherited knowledge into his work. This is a theme that is repeated in the work of Bofill. It evolves from imitation of the vernacular, as in this case, to a more refined interaction with tradition, in the shape of what he calls “critical regionalism.” He learned about traditional building techniques—the Catalan vault and its tiling, for example—and he tried to contrast these ways with his ideas and theoretical logic, often feeling that he was unable to improve on tradition.

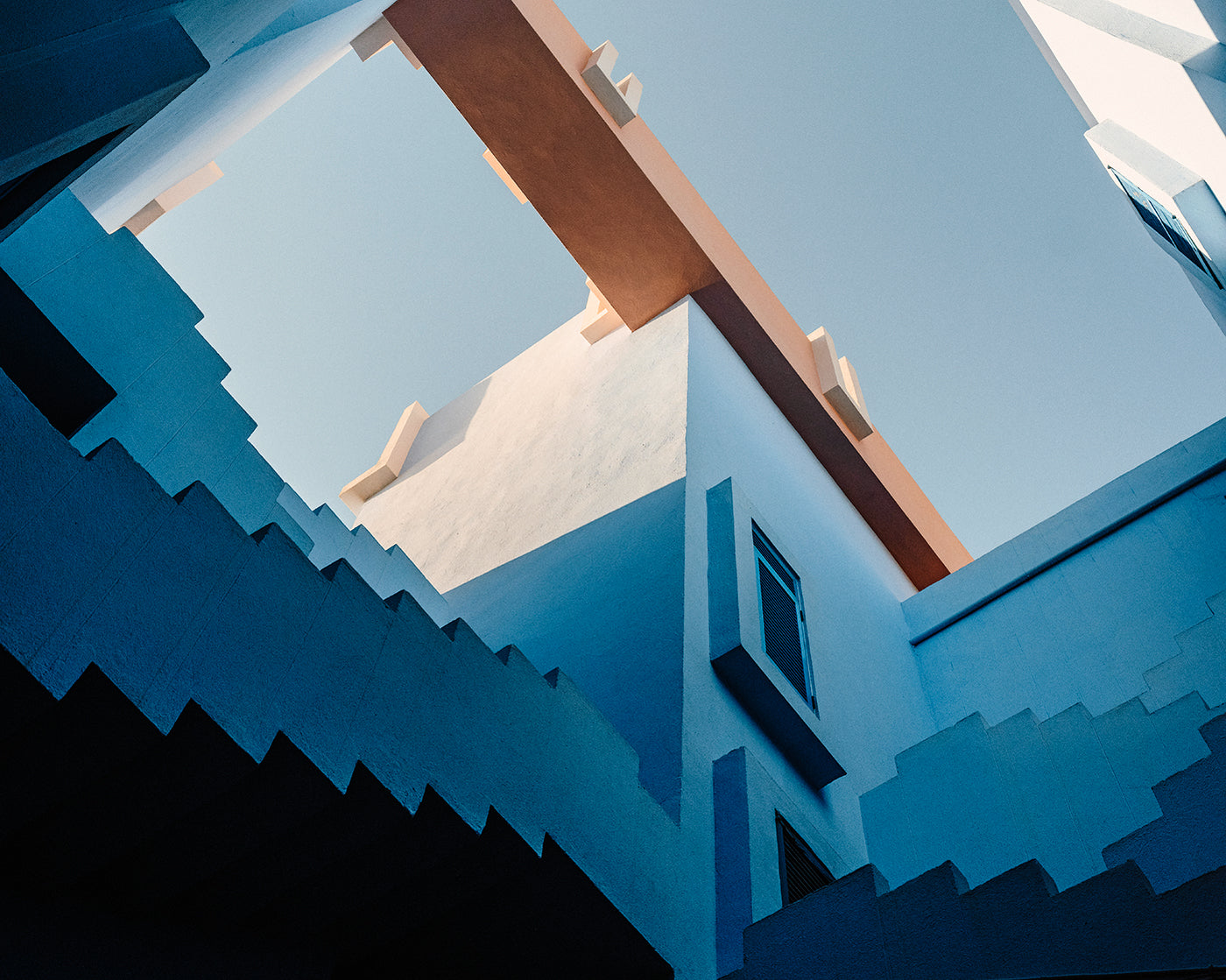

Without leaving these lessons entirely behind, Bofill in the late 1960s quickly moved into a new phase of work: bigger, ambitious, and political. In the postmodern exuberance of projects like the Gaudí District, Kafka’s Castle, La Muralla Roja, and Walden 7, inspiration moves from the futuristic ideas of pioneering UK architecture collective Archigram to a more personal, traveled aesthetic, rooted at the same time in local tradition. Postmodernity in the work of Bofill does not have to be the abolishing of rules or the death of history. In his own words, postmodernity “breaks with cultural hegemony to adapt models to different cultures, considering the place and its history.” It is more of a reaction against the uniformity of modern architecture.

Launched in the early 1970s, The Taller was a kind of commune of different types of artists, poets, painters, philosophers, and also architects

Regardless of the style of their classification, several qualities characterize Bofill’s work at any given time. What Bofill creates with exceptional mastery are spaces or the sense of space. He describes this ability, probably jokingly, as being an escape from the claustrophobia of his childhood in Barcelona, living in bourgeois apartments crammed floor to ceiling with decorative objects. Despite his saying this, many of his vast spaces work because they are in conjunction with other small ones. The huge living room at La Fábrica makes the small bedroom hanging on top of it beautiful and harmonious. It’s the minimal apertures in the facades of Walden 7, opening on to vast internal spaces, or the open square at Les Colonnes de Saint Christophe in Cergy Pontoise, which signifies the small apartments surrounding it. It’s the public spaces combined with the private. And while the public spaces are always majestic, monumental, the private spaces, though intended for retreat and withdrawal, retain, despite the difference in scale, some of the same nobility.

The upstairs living room at La Fabrica features reproduction Gaudi chairs and tables designed by Bofill, hewn from red marble from Alicante. (Photo: Salva López, Ricardo Bofill - Visions of Architecture)

Another characteristic of Bofill’s work is his consideration of it as art. We see this through the force of expression present, and the work’s monumental features. Teleologically, the forms are justified by a search for beauty over all other aspects, beauty, in Bofill’s case, being both the inspiring source and the goal of all elements of style. The idea of Bofill as an artist is interesting since he’s completely aware of the limitations of his practice. Having written books and directed films, he decided to focus on his architecture, which is precisely the least individual of all the arts. He understood early that to be an architect one has to encompass many areas of knowledge, and that this is something that can’t be done alone. Launched in the early 1970s, The Taller was a kind of commune of different types of artists, poets, painters, philosophers, and also architects. Although in terms of buildings planned this wasn’t the most productive period for the studio, it probably established the basis of Bofill’s work and thought for the rest of his career, and many of his long-time contributors have been with him since this era.

Bofill’s commitment to the Taller over his persona is obvious from the first visit; there are no pictures, nothing devoted to the person leading the team. Decorations, or decorative objects, are scarce, considering the size of the complex, with large models, framed plans, and drawings of the buildings the only decoration, besides the books and many ashtrays. The few works of art in the whole building—including his private rooms—are a beautiful Baroque painting, a picture of his parents, and two or three Picasso lithographs. There is a nice set of Charles Rennie Mackintosh chairs in one dining room and a beautiful set by Antoni Gaudí in another, but most of the other chairs are Thonet’s model no. 30. It is not minimally furnished; neither are the spaces empty. But the furniture is there to serve a purpose, not to outshine the rooms in which it stands. The fact that Bofill’s ego and all that is accessory to it is in a very secondary position in the mise-en-scène increases the feeling of being in a sacred venue, in a place that does not belong to one person, and that will live longer than any of its inhabitants. It’s a monument, a monastery devoted to an idea of life, and inside the monument, the person disappears.

La Muralla Roja represents a bold and colorful gesture, the faded reds and pale blues of the complex echoing the distinctive palette of the surrounding Mediterranean landscape. (Photo: Salva López, Ricardo Bofill - Visions of Architecture)

The last time I met Bofill was at another wedding. It’s a summer night by the Mediterranean Sea and music’s playing. He’s holding a cigarette, surrounded by his clan: architects, writers, a philosopher, even a Berber shepherd, all bound together by his exceptional figure and by a long-lasting commitment to his practice. I look at them, nostalgic, as they represent the last dreamers of modernity, and also jealous, as they encapsulate for me all the virtues, the fulfilled dreams, and grand ambitions that I feel my generation has not been able to have. Bofill himself is at the center of all this—dreaming and building on a grand scale, striding out of reach as he fixes his sights on the next great challenge.

Discover Ricardo Bofill through our unique monograph on the radical visionary of architecture.