The Long Road to The Porsche 911

An iconic design changed automobile history in 1963, grasp the moments and events that paved the way for the 911

When Ferdinand Alexander Porsche entered the family business in 1958, he filled an unknown vacuum. An experimental visionary who wanted to challenge tradition, he elevated the design legacy of this famous German brand. From working in the engineering office to craftily creating an icon amongst sportscars, writer Ulf Porschardt reveals how Ferdinand Alexander’s sketches evolved to become a cultural symbol.

The family pictures of Ferdinand Alexander often show him and other children in the proximity of cars, engines, and Vespa scooters. The garage frequently replaced the living room. Accompanying his father to motor races as a young boy to watch his creations compete, he knew what was expected of him. He attended an independent Waldorf school in Stuttgart from where he transferred to the Ulm School of Design, a style-defining institute that set out to continue the Bauhaus legacy in post-war Germany. He only stayed for two semesters, after which he felt to have seen enough.

At the time, Porsche was a company without designers. The self-confident engineers considered it superficial and something of a luxury to think about design. The first Porsche, the 356, was a functionalist manifesto. The first prestigious Porsche salesroom on Park Avenue in New York was designed by the elderly Frank Lloyd Wright, whose final works also included a house for the Porsche importer Max Hoffmann built at the gates of New York. In pictures featuring a Porsche in front of Wright’s late work, the colors and forms of both house and sports car appear related. They were messengers of a new age that had already begun and whose victory was imminent.

A dramatic display at the Max Hoffman showrooms designed by Frank Lloyd Wright on New York’s Park Avenue around 1954/55. (Photo: Porsche Archiv, Porsche 911)

The aerodynamics, the lightweight material, and the maximum economy in the dimensioning of the vehicle had shaped the design. When Ferdinand Porsche, known in the family as 'Butzi,' began working in Zuffenhausen, Erwin Komenda was the recognized authority when it came to bodywork construction. Three years prior, Ferry Porsche had promoted him to chief engineer, so it appeared natural enough to the sober-minded man in his mid-fifties that he would be responsible for the form of the 356’s successor. Since the end of the 1950s, it had been clear that the small, lightweight sports car, directly descended from the Beetle, had reached the end of the road technically. A completely new vehicle was needed. More room, more power, and more contemporary technology! At the end of the 1950s, there were faster cars on the freeway.

Capitulation to the zeitgeist, that demanded flamboyant designs and a break from the Porsche non-design autopoiesis

Back in 1951, Erwin Komenda had designed a four-seater version of the 356. In a somewhat brutal fashion, he extended the wheelbase of the delicate sports car by 30cm (12in.) and exchanged the previously compact doors with massively proportioned versions. This enabling feature allowed passengers to climb into the coupe’s rear compartment. The experiment was called type 530 and lacked the charm of minimalist sculpture. The creature looked bulky and erratic. The car was too heavy for the souped-up four-cylinder and was therefore never considered for production. However, the question of whether a new Porsche should be a full-blown four-seater or a smaller 2+2 remained open. Ferry Porsche was uncertain about this issue for some time. During the entire second half of the 1950s, Ferry Porsche commissioned designs that allowed for sufficient seating comfort in the rear as well as a larger trunk.

The quasi-natural evolution of the 356 from the Beetle threatened to become a dead-end, an automotive cul-de-sac without a living heir. The bodywork manufacturers, Reutter in Stuttgart and Beutler in Thun, Switzerland, received contracts to construct elongated 356s.

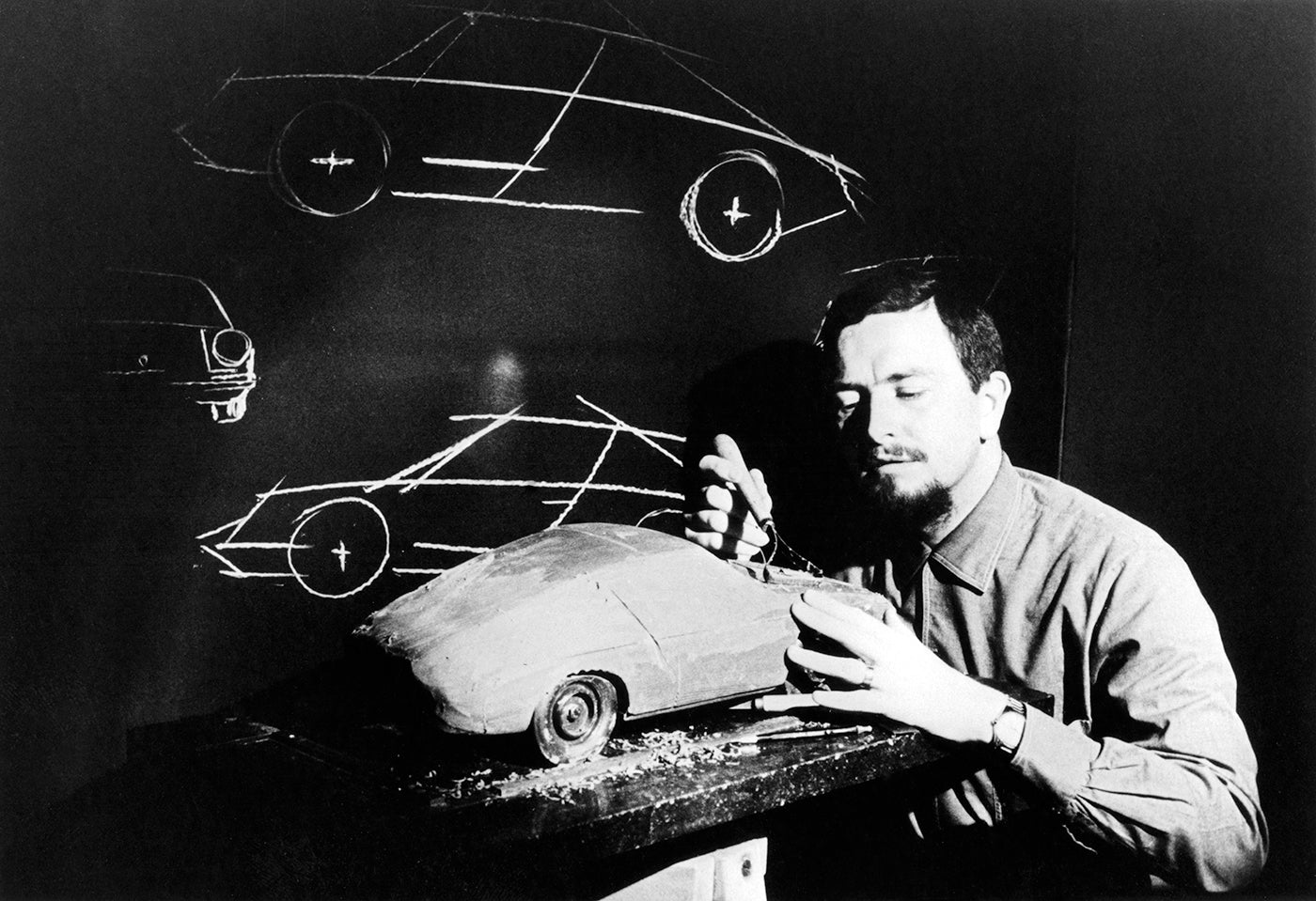

A prototype Porsche 530 four-seater from circa 1952/53 (above), and a Porsche Type 695 (below) being configured in the Zuffenhausen design department. (Photos: Porsche Archiv, Porsche 911)

After the designs and suggestions from these companies failed to produce any convincing results, Ferry Porsche invited Count Albrecht von Goertz, the 'hip' car designer of the time to design the new Porsche. Capitulation to the zeitgeist, that demanded flamboyant designs and a break from the Porsche non-design autopoiesis. With the BMW 507, presented at the IAA in 1955, Count Goertz had created a roadster that set new standards in the combination of elegance and sportiness. With its 150hp, eight-cylinder engine-its gentle Mediterranean forms, the BMW was a serious rival to the 356, which in comparison looked almost dainty. Heady with success, Count Goertz designed a prestigious, muscular sports car for the Zuffenhausen-based company that was more reminiscent of a Ferrari or a Maserati.

At the front, the car was fitted with hyper-thyroidal double headlights while the rear was lit up by six small flashing lights. Besides, there were massive, by Porsche standards, almost baroque bumpers. What Count Goertz presented, in a rather theatrical form, was the glitter and glamour of the 1950s, and for this reason, it was rejected by the down-to-earth Porsches. The aristocrat, who worked for Raymond Loewy in New York after the war, had designed a “very beautiful car.” Nevertheless, Louise Piëch and Ferry Porsche agreed: it was a Goertz, but not a Porsche design.

The Goertzian design was in love with the grand gesture. The same year Roland Barthes declared the car to be the equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals, and in his popular and shamelessly cited work Mythologies, considered it a major creation of the epoch, passionately conceived by numerous nameless artists. In the style of pop art, Barthes enacted an intellectual and cultural upgrading of the automobile, without the hyper-modern pathos of the futurists. The Citroën DS—automotive darling of the French post-structuralists—with the pompous nickname Déesse, meaning goddess, offered such bold theses a generously dimensioned sounding board. As if descended from heaven, it appeared to the poet as a superlative object: completely new and without origin, slick, science fiction. The DS, with its streamlined bodywork and hydropneumatic suspension, was, without doubt, an innovative car; however, it was innovative in a brash, comparatively obvious fashion. Like Goertz’s design, there was something theatrical about the way this Citroën paraded its inner and outer qualities. “NEW” was written above both of them in huge, brightly lit letters. It was the antithesis of the compact functionalism and traditionalism of Porsche.

The development of the Count Goertz-designed Porsche Type 695 in February 1958. (Photo: Porsche Archiv, Porsche 911)

The idea that innovation and the new were dependent on a gift from heaven appeared absurd to the mechanics in Zuffenhausen. He risked a second design, christened “Junior,” so that Porsche ended up rejecting two of Goertz’s ideas—“and that was the end of my collaboration with Porsche,” as the nobleman concluded, almost amused. Nevertheless, he remained on good terms with the Porsches privately, even claim- ing to have lured Ferdinand Alexander Porsche into the family business from the Ulm School of Design.

At the age of 22, Ferdinand Alexander Porsche encouraged in his free creativity by the Waldorf school, entered Erwin Komenda’s design department. As well-known as Count Goertz may have been, the ultimate authority in the department was Komenda, but not for long. Ferdinand Alexander had completed a two-year internship at Bosch before starting his studies in Ulm, so he had no problems tackling design concepts dominated by technical issues.

“The whole of humanity is getting bigger, the car has to be bigger too”

The young man had a sense that he would encounter the aesthetic functionalism of the Ulm school in its purest form in Porsche’s engineering offices. The intellectualism and theorizing cultivated in Ulm was not his thing anyway. He wanted to create, not talk. A colleague from the model department named Heinrich Klie suggested a few details during the preliminary work that Ferdinand Alexander could build on, and he intended to. They concerned the relatively high fenders compared to the 356 and the integrated headlights, as well as the austere chrome strip on the front hood.

The young Porsche grandchild was not only confident enough to use the department’s preliminary work, but also the employees. Thanks to his familiarity with these people and their work, and intimacy that he had shared since childhood, he had a certain natural affection for them. They worked in his family’s company and were thus somehow part of the clan. At any rate, this feeling of intimacy and trust was something cultivated by the father, Ferry Porsche. For Ferdinand and Ferry Porsche the employees were “their people, members of their family,” recalls Herbert Linge who was awarded his apprenticeship by Professor Porsche personally and remained loyal to the company until his retirement.

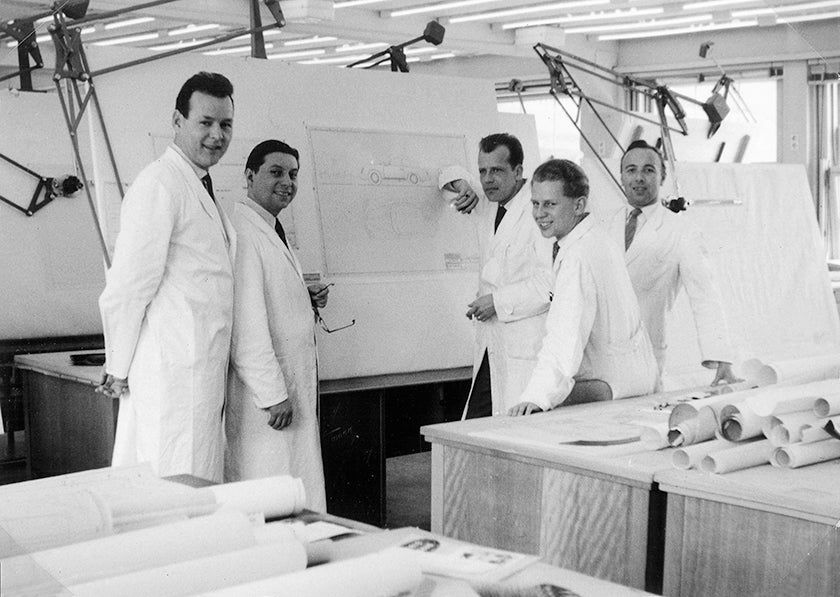

Porsche’s designers Willi Vetter, Karl Vettel, Georg Urbanczik, Rudi Maier, and Walter Huettich in 1958. (Photo: Porsche Archiv, Porsche 911)

There came a point when Ferry, who had brooded and puzzled over the definition of the 356’s successor for a long time, recognized to his horror that the road to more room led away from the recently established myth of the compact and light sports car. For Ferry Porsche, it was clear that they "occupied a very nice niche,” and that others are better at producing limousines, which is why he decided to hone Porsche’s freshly acquired core-competence. His son understood him instinctively and the most clearly of all. Ferdinand Alexander’s type 754 T7 was produced in the space of a few weeks between the end of August and the beginning of October 1959. At the time the “designer” was not even 24 years old. The front section was almost identical to the later serial version of the first 911's. As the T7 was still mounted on a four-seater chassis, the silhouette still lacked the compactness and the rear elegance of the later 911. However, this quickly changed.

Ferry Porsche was happy and proud of his son’s design. However, he had the feeling that the young man and his design weren’t taken seriously by everyone in the bodywork department. In his memoirs, he described it idiosyncratically as an undesirable development that came from the offices—against his will. His employees justified the fact that the car was getting bigger and heavier with platitudes such as “the whole of humanity is getting bigger, the car has to be bigger too.”

Ferry Porsche with his son Ferdinand Alexander in the Zuffenhausen factory yard in 1964. (Photo: Porsche Archiv, Porsche 911)

After countless discussions, the wheelbase was reduced by 10cm (4in.) again. This lent the Porsche more harmonious proportions. The bulky protrusion on the tail, designed to give rear passengers more headroom, disappeared. Porsche relinquished the idea of a sports car that provided travel comfort or even an acceptable seating position for four adults.

The forms were gentle and the car’s face was benevolent. The 911 dispensed with an aggressive aesthetic

Finally, Ferdinand Alexander was commissioned to design a coupe based on the T7, which, instead of containing four seats, would provide just two proper seats and two jump seats. The new Porsche was to be powered by an air-cooled, six-cylinder motor with overhead camshaft, and have the road performance of the 356 Carrera 2, which extracted 130hp from the four-cylinder boxer engine and had a top speed of 210km/h (130mph).

The T8 was developed, and Ferdinand Porsche enlisted two technicians into his team to prevent the designs from lapsing into the artistic. The humility of the son in the face of the engineering spirit of his father and grandfather was not reverential but constructive. He made the engineers his allies in the development of the design ideas. The result quickly proved worth seeing. It was the first Porsche 911—the vision formed.

The interior of a functionalist manifesto: the dashboard of a slate-gray 1958 Porsche 356A. (Photo: (Photo: Porsche Archiv, Porsche 911)

The model already had the side window architecture that has remained to this day. The roofline had found its proportions, the relationship between the raised fenders and hood had been established. This topography above the hood dramatized the tendencies that could already be detected in the profile of the 356. Now the lamps had become gun barrels, as the designers in Weissach say, or that décolleté which makes the hearts of millions of men—and also women—beat faster. The forms were gentle and the car’s face was benevolent. The 911 dispensed with an aggressive aesthetic and began as a coupe whose road presence would exude a natural functionality and confidence derived from its performance.

The Porsche didn’t need and didn’t want to prove anything to anybody. Following the completion of the first model, the work merely consisted of refining a successful form, which, no one could have predicted at the time, would endure for over half a century. The first one-to-one model followed a short while later, constructed from wood and sheet metal. It was presented to the management board on April 16, 1962, and accepted. The same year the prototype in the form of the 901-1 was built. The collaboration between father and son had born fruit. Ferdinand Alexander Porsche recalled, “When I was constructing the 911, he stood right behind me from the beginning. Not because I was his son, but because he was convinced. He always had a highly developed sense of form; he never liked extreme colors and forms.” Father and son looked at the 911 and both saw themselves in it. An ideal case for a family business.

A symbol of aspiration and resistance to normality, this favorite is the raw story behind the legendary Porsche 911.